Moved to tears

20 years ago, on January 15 2004, a little before 2 AM Pacific time, was the payoff.

Spirit successfully drove onto Mars. Three meters straight forward, across its black composite lander, and down a pale yellow ramp, 6 wheels rolled to a stop on the dusty red soil the rover was designed for. I was leading the operations team as Flight Director. For many long days and late nights before, I was one of hundreds of engineers who contributed to that successful moment.

It was cause for celebration. But first, I wept.

It worked. We did it. Tears of joy. Me (center), my friends Kevin (right), Richard (left), and Eddie, Ashitey, and Brian from left-to-right in the background.

I would have forgotten that particular detail except a member of the press captured it and published it to the world. [1]

I was mortified.

That 24-hour period was one of the busiest and highest-stakes days of my life. Roughly 12 hours earlier I awoke in the middle of the Martian night and rushed into NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab (JPL) so that my teammates and I could meet Vice President Cheney, and present him a gift of a Mars Watch, and the next day President Bush would announce his new Vision for Space Exploration. After a trip back home to catch a nap, I returned to perform the task I had been working on every day of the prior three years; drive the Spirit rover safely onto Mars.

In the mission support area, as we sent the command to egress, I commented that this was “perhaps the most significant 3 meter drive in recorded history.” To me, it certainly was. After surviving the “Six Minutes of Terror” of Entry, Descent and Landing, and then successfully unfolding the robotic origami that would birth a rover, I did not want its first and only steps to be a face plant. [2]

Despite realizing a dream I’d had for 15 years — half my life at that point — and despite great uncertainty and stress, I still remember feeling self-conscious about those tears being featured on what seemed like every news article. The JPL media team assured me that not only was it OK, it was a wonderful, humanizing moment for a team of supposed brainiacs working on space robots. Joy and relief shared with the team that made it happen.

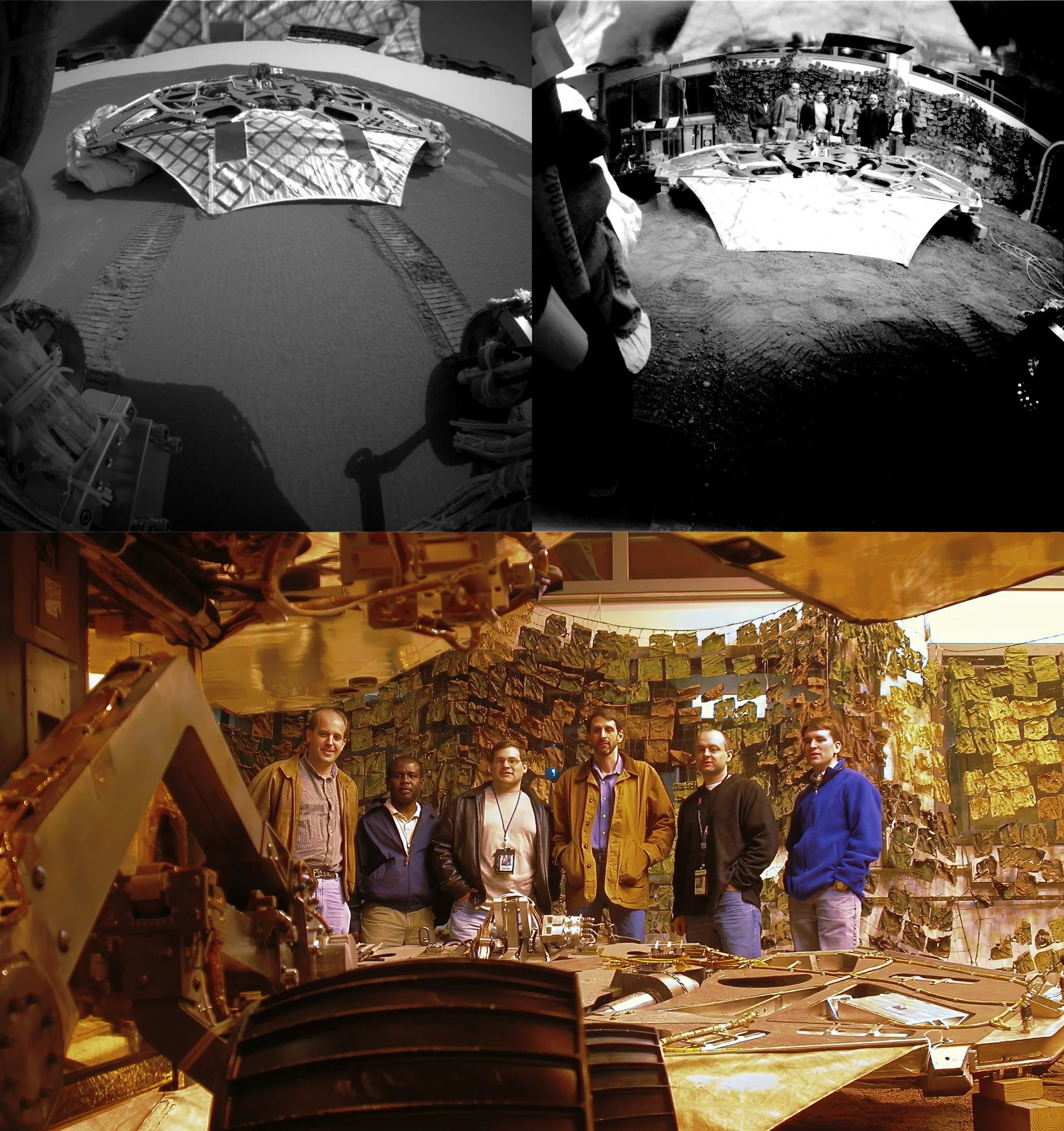

Two for Two. One dozen wheels on soil.

Upper Left: (Mars) Opportunity rear hazard camera image confirming successful egress.

Upper Right: (Earth) Testbed hazard camera image, photo-bombed by the team, confirming successful egress

Bottom: (Earth) Team photo with a better camera

After the rejoicing, tears, and a profound sense of relief, I stepped onto the stage at JPL’s Von Karman auditorium for a press conference. There, with a turn of phrase, I ‘handed the rover keys’ to the science team for their mission in Gusev Crater to follow the water on Mars.

I don’t recall the precise timing of the conversation with my eldest brother Mike, perhaps it was that very night, but I vividly remember his wisdom that brought everything into perspective:

“We should all be so fortunate to work on something that moves us to tears.”

And from that moment on, that’s exactly how I did feel … so fortunate.

That day’s sweet success on the surface of Mars had been realized in an intense period of less than 3 years.

It was a GREAT day.

Leap forward 15 years, from January of 2004 to January of 2018. Another day of tears preceded by a 9-year intense blur of uncertainty and stress. I was the CEO of the space startup Planetary Resources and on that particular morning, there was no cause for celebration or joyous relief shared with a team.

My task that day, I faced alone. I was to begin laying off my team and winding down the company. For almost a decade, we had dared to pursue the inspired dream of asteroid mining. I had endured the monthly, weekly, then eventually hourly struggle to build an improbable company. Along with that struggle were turning points in careers, stress and uncertainty for families, and in the end, a shared experience of failure.

The day was bookended with tears. Mood of self-induced bomb blast and aftermath.

It was a HORRIBLE day, with many more somber days to follow.

These moments usually fade into memory, undocumented. Photographers aren’t summoned to capture these experiences. We forego press conferences, and reporters’ calls are left to go to voicemail.

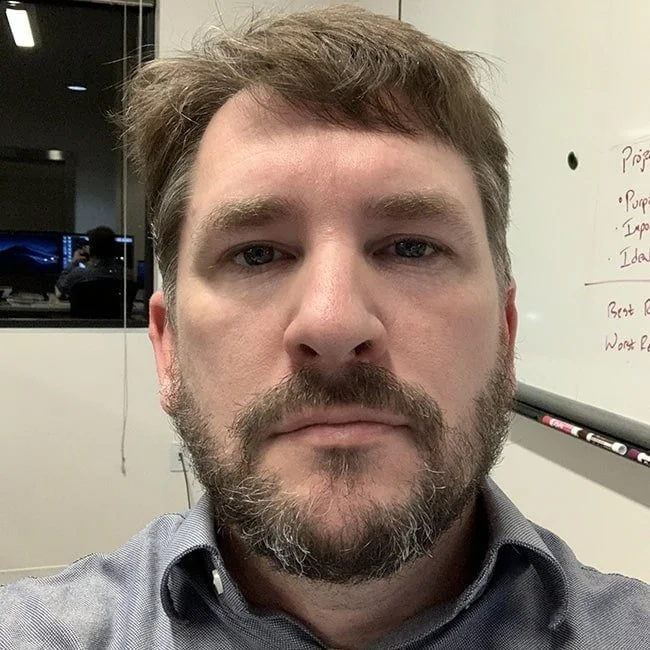

Some somber moment, self-documented, later in 2018. And one of the few pictures of me that year.

We can’t imagine wanting to remember the shadow that accompanies joy — anguish.

And yet, when I think of the soaring highs of January 2004 and the miserable depths of January 2018, the two moments are connected by the same thread:

“We should all be so fortunate to work on something that moves us to tears.”

We don’t often see the undesired moments of humanity in public, but we all experience them privately. The triumphs are glorious because the stumbles far outnumber them.

I was fortunate to work on something that so inspired me, that inspired others to join me, and stirred inspiration in those who learned of it. On that horrible day, those were the tears of failure while daring greatly. I was fortunate to feel the loss profoundly. It was a testament that, for a time, it was something wonderful and inspirational.

With memories of the heights of success and the depths of failure behind me, I've come to understand that my true pursuit in work is inspiration.

To find it, to be it, to build it, is the ultimate fortune. May it favor your path as well.

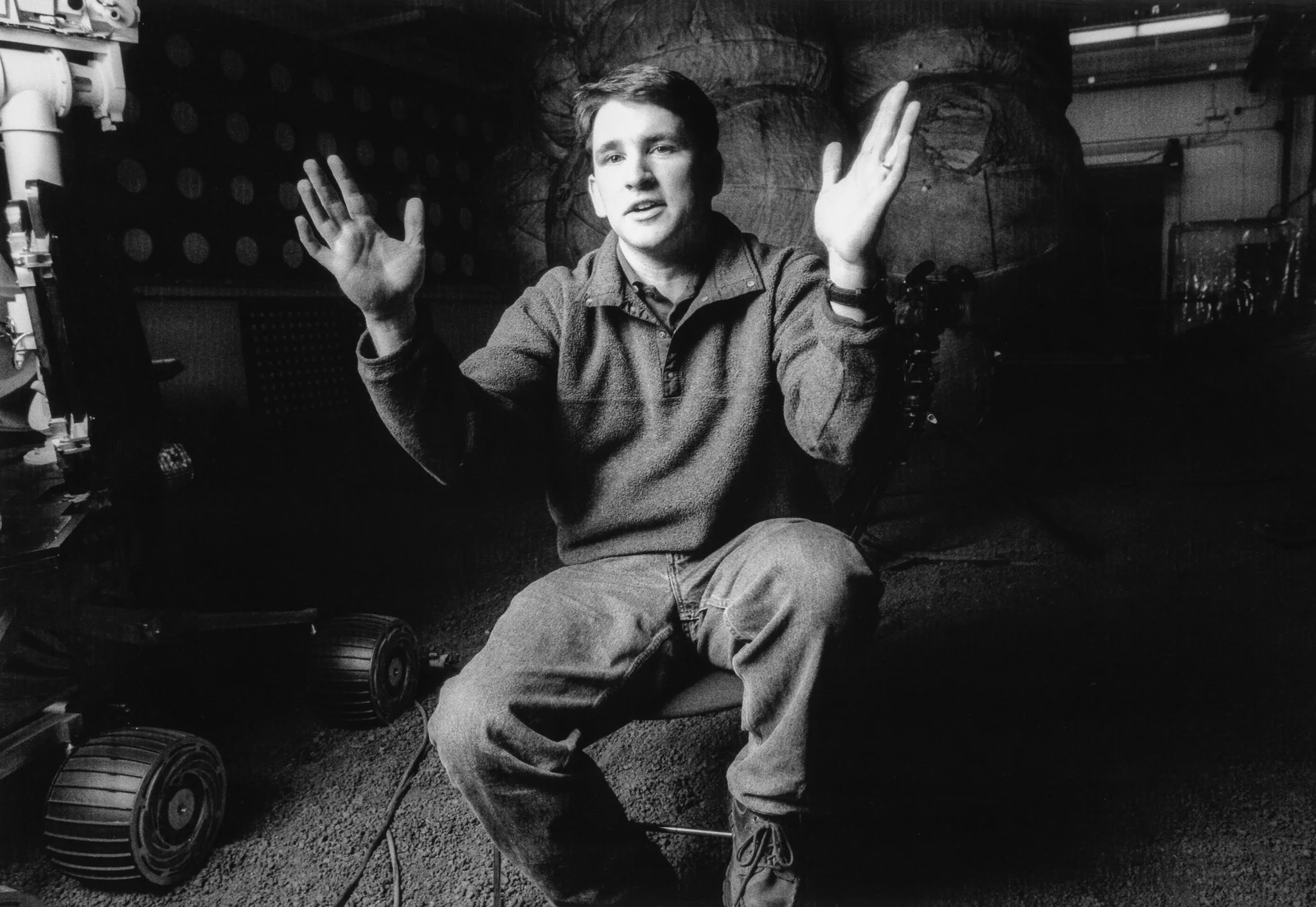

Chris Lewicki as photographed by Norman Seeff (2004). I first shared this story during a photography session in JPL’s Mars testbed [3], a session I was assisting with, and the listener was none other than Norman Seef [4]— the legendary rock and roll photographer whose iconic images are instantly recognizable.

Belated thanks to REUTERS/Ric Francis for the treasured memory. http://www.ricfrancis.net/

J. Krajewski, K. Burke, C. Lewicki, D. Limonadi, A. Trebi-Ollennu and C. Voorhees, "MER: from landing to six wheels on Mars...twice," 2005 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 2005, pp. 1791-1798 Vol. 2, doi: 10.1109/ICSMC.2005.1571408.

Norman Seeff's the Sessions, Episode 10. I’ve never actually seen this episode, but would be curious to know how I expressed the feeling 20 years ago. Alas I’ve not been able to access it.

Thanks to Mike Lewicki and Andrea Lewicki for reviewing drafts of this piece.